The challenges of preserving Midcentury Modern homes

By Katherine Salant — The Washington Post

October 5, 2012

When it comes to historic preservation, every generation is dismissive of buildings from the recent past in favor of those that go further back in time.

As Rice University architectural historian Stephen Fox put it, “Each generation has its own ignorance of recent stuff.”

In the early 20th century, preservationists referred to the Victorian era as “the dark ages” and eschewed its buildings for colonial and federalist-styled ones that predated them, Fox said. Twenty-five years later in the 1950s and 1960s, the preservationists deemed all things Victorian to be the “cutting edge of taste,” but derided 30- to 40-year-old Art Deco-styled buildings as “too decorative.” In the 1970s and ’80s, this style was embraced for the same reason it was once dismissed.

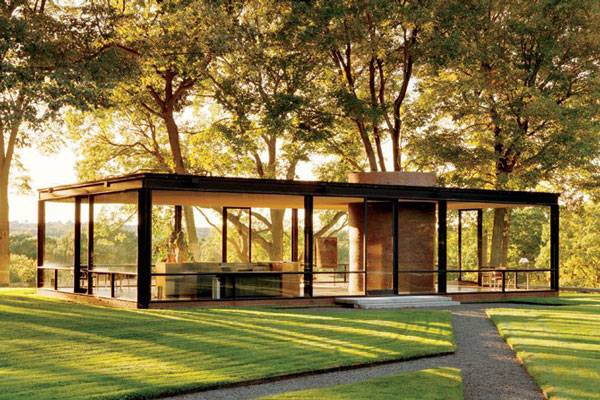

For the current generation of preservationists, the style that’s not worth saving is Midcentury Modern — those buildings and houses that were built from about 1945 to 1965.

Though not surprising, given the pattern of preservationists’ evolving enthusiasm, there is a certain irony in this particular repudiation. The informal lifestyle that homeowners today prefer originated with this style and its most salient features are still wildly popular — an open floor plan with adjacent living, dining and kitchen areas, and large sliding glass doors that open onto adjacent decks and patios, blending indoor and outdoor living areas.

Some of the antipathy toward Midcentury Modern, which has existed since the style was first introduced, can be attributed to its very different look. Most houses of that style featured flat or nearly flat roofs, unusually large windows and a total absence of any of the traditional embellishments normally associated with houses, such as shutters.

Although the houses looked different, many of the architects who pioneered this style cleverly combined the new look with longstanding vernacular housing traditions that had evolved in response to local climate. In Sarasota, Fla., for example, the first Midcentury Modern houses were built before air conditioning was available. To create cross ventilation — essential with Sarasota’s debilitating heat and humidity — the architects replaced the many small window openings found on older houses with two or three huge rolling panels of glass that were often 8 feet high and 10 feet long, so large that it looks as if there’s no wall at all.

When these panels are fully opened to catch the breeze, the line between indoors and outdoors literally dissolves. The visual effect is stunning, but the comfort level is even more impressive. Although air conditioning was eventually installed in all the Midcentury Modern houses that are still standing, it often goes unused for as many as 10 months of the year. Sarasota architect Sam Holladay, who lives in a Midcentury Modern house himself, uses the air conditioning only during June, July and part of August, and the year he moved in, he said, “I was amazed my power bill was so small.”

In addition to astounding visuals and a high degree of comfort, the homeowner who decides to restore a Midcentury Modern house can, in many cases, achieve a degree of authenticity that is nearly impossible with older houses. The architect himself and people who worked with him or who helped to build the house may still be alive, the original drawings are far less likely to be lost, and there may be photographs of the original furnishings.

When Holladay restored the 1955 Cohen House by Paul Rudolph, the most famous of Sarasota’s Midcentury Modern architects, he was able to consult an architect who had worked with Rudolph and study photographs of the house taken at its completion. A colleague also traveled to Washington to examine the Rudolph archive in the Library of Congress. An intriguing result of this research: Holladay was able to re-create the long-gone built-in furniture for a conversation pit. Though Rudolph’s version of a conversation pit is only 8 inches below the adjacent living area, Holladay said, “It’s enough to become its own gathering area during parties.”

Old home movies and family photo albums that document how a house was actually lived in and what should be emphasized in a restoration are another important resource, said Houston architect David Bucek. When his firm was tapped to restore Neuhaus and Taylor’s 1960 Frame Harper House, the entire structure, both inside and out, had been painted white and the kitchen and master bath had been ripped out. The color photographs in the albums of the original owners helped Bucek and his partner Bill Stern determine the original color scheme and what their furnishings looked like and understand how the family used the spaces. They were also able to interview one of the daughters who grew up in the house.

Not all Midcentury Modern houses have such extensive documentation, however. Thousands were constructed by anonymous builders and radically altered by subsequent owners. To bring such a house back to life, Sarasota architect Greg Hall said he’s taken artistic liberties while honoring the “push the envelope” spirit of that era.

This often requires a degree of inventiveness that matches that of the original designers because modern-day fixes must meet more stringent building codes and safety requirements, Hall said. For example, the huge 8-by-10-foot sliding glass panels that were a hallmark of the Midcentury Modern style in Sarasota are no longer allowed, so any rebuilt glass walls will have much narrower sliders. When these are closed, you see the vertical lines of the frames and know that you’re inside. But when the doors are fully opened, the line between inside and outside dissolves, just as it did in the original houses.

For his “Garden House,” a reimagined restoration of a 1960 Midcentury Modern tract-built house, Hall took the glass wall idea one step further. Two walls of sliding glass doors in the living room pull back from the same corner. When the doors are fully opened, the wall dissolves and half the room is completely open to the outside.

Should an episode of the television drama “Mad Men” that’s set in the 1960s take place in Florida, Hall’s Garden House would be a perfect location shot. One can easily imagine Don Draper emerging through the opened glass walls of the living room to lounge on the adjacent patio and sip an Old Fashioned as he watches the sun slowly sink beneath the horizon.

Katherine Salant has an architecture degree from Harvard. A native Washingtonian, she grew up in Fairfax County and now lives in Ann Arbor, Mich. If you have questions or column ideas, she can be contacted at salanthousewatch@gmail.com or www.katherinesalant.com.