A Gut Renovated MidCentury Modern Green Energy Home for Luxury Winter Living for $4.65m

A Mid Century Custom Renovated Treasure with additions designed by Paul Rudolph with custom finishes of the finest caliber throughout. Gut renovated with all new systems (plumbing, electric, HVAC, AV, internet, floors, walls, windows, outdoor and indoor kitchens, baths, indoor and outdoor pools, landscaping, roofs, decks) completed 2020, on the market for an asking price of $4.649 million.

This 10,000+ Sqft complex includes the main residence, separate apt or office, a Paul Rudolph original guest house. A rare and priceless offering perfect for sheltering in place with indoor and outdoor swimming pools, wet/dry sauna, media room, gym, multiple workspaces.

A 1000+ Sqft screened-in outdoor covered porch with an entertaining outdoor kitchen overlooking the outdoor pool,

Imagine living in this luxury house sited on a unique 2.48 private landscape in Larchmont this is a truly unique mid-century modern green home retreat. A perfect shelter-in-place home with easy access to NYC.

Multi-zone radiant heating and cooling, which creates an ambient temperature throughout the house with 7 zone controls. A pleasant warm feeling on your feet and no hot or cold spots.

Central Humidity control – the humidity levels in the house are controlled by a central humidity control system. It pumps humid air, to avoid excessive dryness in winter, and dehumidifies the house, when the weather is humid.

An indoor pool and jacuzzi – where the entire family can enjoy the snowy weather outlooking the window walls, with a warm pool day across a dual-sided gas fireplace.

A wet-dry sauna and indoor gym – to warm you up and keep you going through the cold days

A master bath, with digital temperature controls and a steam shower.

A 21 jet jacuzzi tub in the master bath for privacy.

Heated toilet seats and heated bidets throughout all bathrooms in the house.

Walls of windows, and skylights for amazing natural sunshine through the dark days of winter.

And, if you think this is going to run up a huge energy bill, it’s a “zero” energy house with geothermal and solar systems, with a 45KW whole house generator backup, for when the snowstorm knocks your power out. Luxury at its finest.

Visit website at 862Fenimore.com

For additional architectural photography:

– Exterior –

www.862fenimore.com/est…

www.862fenimore.com/est…

– Interior –

www.862fenimore.com/est…

– Interior –

www.862fenimore.com/est…Betty McDowell

uploaded A Gut Renovated MidCentury Modern Green Energy Home for Luxury Winter Living for $4.65m through Add A Home.Add your own project for the chance to be featured in Editor’s Picks.

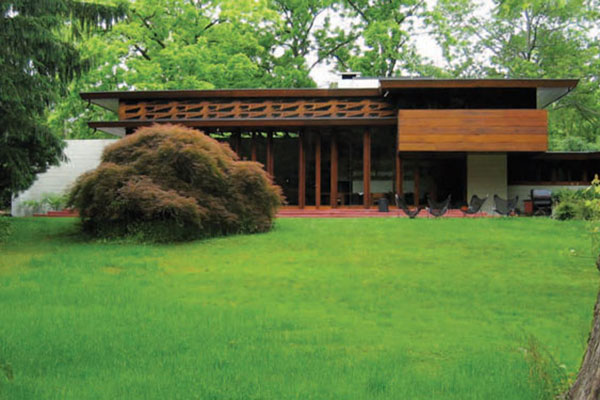

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:exterior, flat roofline, house building type, shingles roof material, wood siding material

Front

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:bedroom, ceiling lighting

Master Bedroom

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:exterior, wood siding material, flat roofline, house building type

Entrance and canopies

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:exterior, house building type, wood siding material, flat roofline

Paul Rudolph designed canopies

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:exterior, house building type, flat roofline, wood siding material

Lower level entrance

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:outdoor, large pools, tubs, showers, trees

Outdoor Pool and Backyard

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:exterior, house building type, wood siding material, flat roofline

Exterior from the side

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:dining room, two-sided fireplace, ceiling lighting, gas burning fireplace, recessed lighting

Dining Room overlooking leveled living area

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:exterior, flat roofline, house building type, wood siding material

Canopies from the side

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:living room, ceiling lighting, two-sided fireplace, gas burning fireplace

Living room

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:living room, ceiling lighting, gas burning fireplace, two-sided fireplace, light hardwood floors

Leveled living area

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:outdoor, large patio, porch, deck

Screened Porch with full kitchen overlooking backyard and outdoor pool

Photo: Paul Rudolph Heritage FoundationPhoto Categories:living room, ceiling lighting, recessed lighting, floor lighting, accent lighting

Indoor Pool with Jacuzzi

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:living room, ceiling lighting

Sunroom overlooking Indoor Pool

Photo Courtesy of Betty McDowellPhoto Categories:kitchen, refrigerator, granite counters, ceiling lighting, cooktops

Kitchen with Skylight

Original source can be read from: Dwell